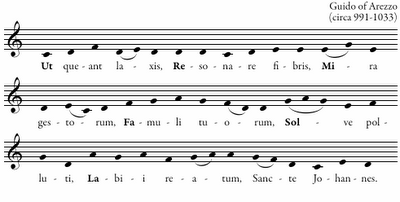

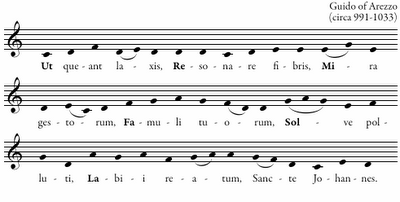

The solfege syllables are one of those commonly used and accepted ideas that seem like they have always existed. These are the familiar do, re, mi, fa, sol, la and ti nonsense sounds for singing a major scale (“Do, a deer, a female deer”). The major scale, and therefor the syllables, can start on any note but C is typically used for examples for simplicity's sake. The syllables can be traced back about a thousand years to Guido d’Arezzo (c. 995-c. 1050 C. E., there are conflicting dates for him), a choir leader and music teacher who developed a new way of training singers to learn music quickly. He wrote a short melody for the chant “Ut queant laxis” (just the notes, not the words) with 6 phrases that all his singers memorized.

Each phrase starts one note higher than the last phrase and began with a different syllable. Each phrase is short enough to remember very easily. Singers used the syllables and notes that began each phrase as stepping stones to find notes in new music without hearing the new music first. This is where the first 6 solfege syllables came from. Do, the first syllable of the scale, was originally ut and the 7th syllable, ti, was added later but the rest are the same. There are a couple of different theories about how these syllables got started but this is the one that turns up in most music history books.

(For the curious, accidentals change the vowel sounds. With sharps, do becomes di, re becomes ri, fa becomes fi, sol becomes si and la becomes li. For flats, re becomes ra, mi becomes me, sol becomes se, la becomes le and ti becomes te. There are other systems and not everyone uses these at all.)

Sometime after these syllables came into use, each syllable/scale-step was assigned to the tips and joints of the fingers so that the choir leader could point to a joint and students would sing that note on cue. In this system, the entire set of syllables are repeated several times since most music has more than 6 notes. Additionally, the repeated sets of syllables are overlapped to show how to modulate to new scales. This technique does not seem to have been invented by Guido but it did use his solfege syllables. The notes, 19 in all, move in something like a spiral around the hand.

|

| Guidonian hand from a manuscript from Mantua, last quarter of 15th century (Oxford University MS Canon. Liturg. 216. f.168 brecto) (Bodleian Library) This image is in the public domain because its copyright has expired. | |

|

This is very complicated and intimidating looking even to professional musicians and not too surprisingly is not used very often these days. But I love the idea of holding two and a half octaves in your hand.

There is a set of hand symbols representing each solfege syllable that some people use today. The hand signs for the sharps and flats aren't used as often.

|

| Ti |

|

| La |

|

| So/Sol |

|

| Fa |

|

| Mi |

|

| Re |

|

| Do |

These are very similar to the sign language alphabet but the two systems have different meanings entirely and the signs for the music syllables are a little more flexible simply because there are fewer. Not every one uses the hand signs for solfege, there are different solfege systems in use and not all musicians use solfege at all.

I am fascinated by the ways we use our hands. It’s an instrumentalist thing as well as a human thing. There is a long list of systems that use the joints or knuckles in the hand as a way to organize, remember and communicate ideas such as musical notes, alphabets, calendar dates and on and on. It's all right there in our hands.

No comments:

Post a Comment